The first time around, I found the experience of being edited…uncomfortable. I handed over a massive chunk of work that I wasn’t really happy with (not to mention how personal it was – there were parts of the story in there I’d never even told my therapist). The person reading it was someone I barely knew but, being an editor at Jonathan Cape, someone I had great reverence for. I left the pages with him, and I waited.

In the time between handing over the pages and our first editorial meeting, my imagination got to work on dreaming up all the possible negative feedback I could receive. Surely Jonathan Cape were now going to realise what a big mistake they’d made, and tell me they were sorry, but they longer wished to publish the book.

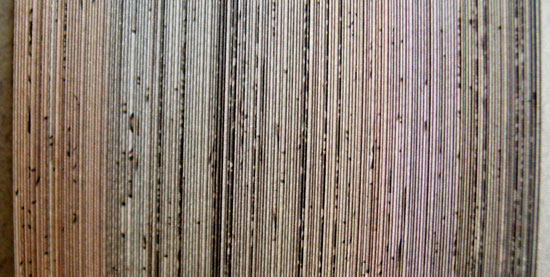

As I travelled to London and walked into Random House, signing my name on my visitor’s name tag, I felt like an imposter. This was something real authors did, not me. Then my mountainous first draft was placed on the table, covered in post-its and green (thankfully not red!) notes…

And my editor told me he liked it.

That’s how I remember the beginning of the professional relationship that really shaped my work on Lighter Than My Shadow. To have that input right from the earliest stages was incredibly valuable. Though it terrified me at first, he was always sensitive and professional, discussing the book almost as a work of fiction, yet never seeming to lack in empathy for it being a true story. Though it made me squirm to listen to and read comments on work I wasn’t happy with, it got easier. I came to appreciate the help and support in working towards something I felt proud of, shaping it into the book I’d started imagining almost ten years beforehand. In time, the relationship became (or perhaps always was, I just misunderstood it) less pupil-teacher, more mutually respectful. A collaboration for the best interests of the story.

Over the following two years we exchanged multiple drafts and redrafts, poking and prodding at the story here and there, taking out entire chunks and sometimes putting them back in again a few months later. Always I got nervous. Always the book got better.

I understand from a recent article written by mine that editors like “to remain invisible, for the work [they] do to be untraceable to the reader; for the book to appear, as Martin Amis has put it, ‘a transfusion from above’, direct from writer’s pen to reader’s eye.” While I value this and agree entirely that’s what a good editor should aspire to, I also think it’s a shame. I don’t like it when people are unappreciated for doing great work, and it’s impossible for me to talk about my creative process without talking about the value of the editorial input I was fortunate enough to receive.

The first time around, I found the experience of being edited uncomfortable, but draft after draft it became easier, and I looked forward to receiving that feedback and support. In the end it was a great pleasure and privilege, enabling me to craft a piece of work to a level I never could have managed alone.

Thanks Alex!