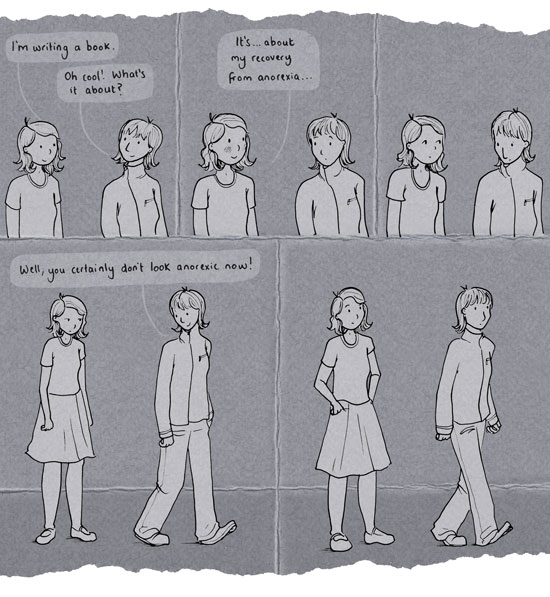

The question I was asked most often whilst working on Lighter Than My Shadow was, ‘Is it cathartic?’ Usually with the assumption that it was, and that was why I was doing it. It’s true that it feels important to get the story ‘out’, but out in the world, not out of me. It’s one of my biggest worries that people will see the book only as an act of catharsis.

That said, I’d be lying if I told you there wasn’t catharsis in the first draft. There was the messy, stream of consciousness getting-it-all-out. But after that, I had to try and put the emotions I was stirring up to one side. I had to make objective* decisions.: whittling down the story to what was essential. What, frankly, was actually interesting.

What I’m trying to say is that working on the book was not therapeutic, and I didn’t expect it to be. Oftentimes I was voluntarily reliving trauma that no longer affected my daily life. If it was catharsis I was looking for, I would have given up when it got hard. If it was catharsis I was looking for, I would have filed it all away in a box when I’d finished, or burned it, or something to that effect. I certainly wouldn’t want to publish it, and I doubt anyone would want to read it either.

So what was I looking for? I’ve written a lot this week about all my lofty reasons for creating Lighter Than My Shadow: breaking the silence, challenging stigma, maybe, possibly helping people. What I haven’t said anything about is this: I wanted to tell a good story. I also just wanted to write a book.

*I had supreme editorial assistance.